Reading Fear with Xavier de le Rue

INTERVIEW Stella Pentti

Xavier delves into overcoming fear, pushing personal limits, the science of snowpack, and sharing unforgettable adventures with family in some of the world’s most extreme terrain.

From straightlining ice walls and exploring some of the most challenging terrain on Earth to educating people on backcountry safety, Xavier de le Rue has been at the forefront of backcountry riding for over twenty years and is considered a superhero of our time. But when you’re known for riding some of the steepest and most extreme faces in the world, not to mention being resuscitated and brought back to life after getting caught in an avalanche, people often fail to remember that you, too, are only human.

Xavier’s relationship with the mountains runs deeper than others. There is a profound love and respect for them but also a healthy amount of fear. Throughout the years, he has grown and evolved with the mountains, learning to manage and read his own fear. As a father of three, a husband, a brother, and a public figure for mountain safety, Xavier has found a way of not letting fear consume him or cloud his judgment.

We talked to Xavier about his most recent film, “Of A Lifetime,” which delves into his freeriding journey. He shares his thoughts on the growing popularity of freeriding, the increased need for accessing the backcountry and how that’s worked as a catalyst for better equipment and more education around safety. Furthermore, Xavier also shares his thoughts on how he has managed his love for continuously exploring the mountains while being conscious of the effects it has on the environment.

Hey Xavier! Thanks again for taking the time to sit down with us. Looks like you’ve had a busy season last year. Want to take us through what you’ve been up to?

It is my pleasure! I went to Norway quite a few times, drove up in a camper van, and filmed a series of episodes for a series called Roamer, which will come out around Christmas. I broke my ribs walking with a surfboard on a flat parking lot, falling onto my surfboard – the most stupid injury ever – so I had to come back home and take a break in between the seasons.

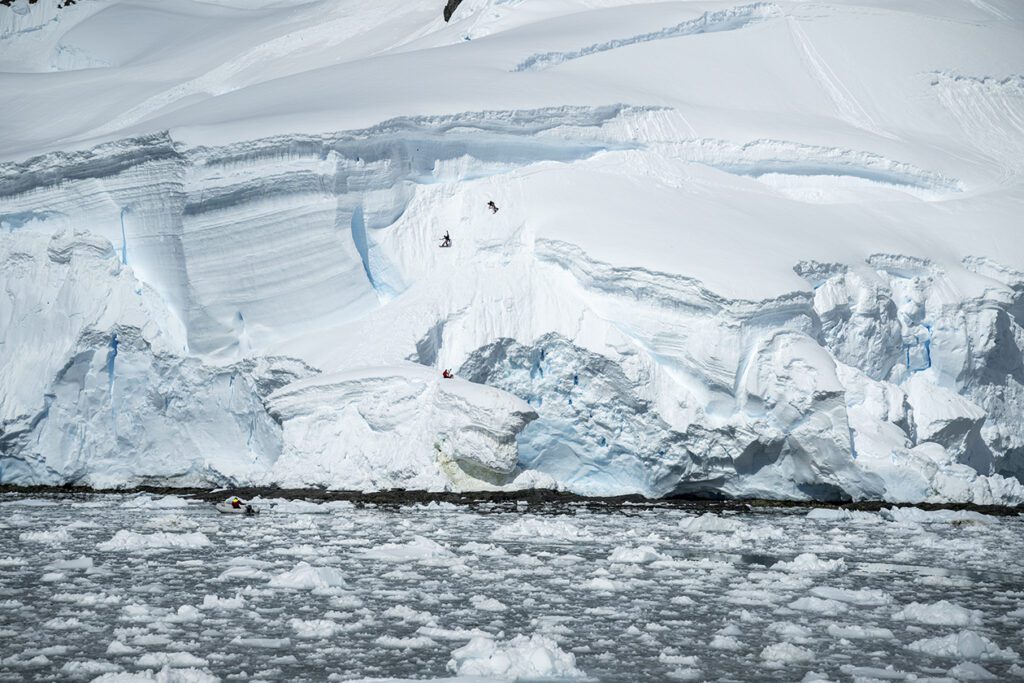

…while also putting together your latest film, Of A Lifetime, that you were filming out in Antarctica with your brother Victor and daughter Mila. How was that experience?

This was the third time that I’d been to Antarctica. It’s by far the most incredible place I have visited and snowboarded in, and I managed to make the trip of my life there about ten years ago. Since then, I have still been traveling quite a lot but never found anything like it. So, this time, it was more about doing it together. Seeing my brother develop and become stronger during the last few years was such a motivation to go down there with him. Taking the opportunity to make a big trip together and share those runs, the place and the adventure with him was something that really really excited me.

The project took quite a few years to organize. My daughter got older and stronger with her skiing, so I was like, why not take her there? With our age differences, with Victor being ten years younger than me, it felt like we were three generations of us going down there together, sharing it together, and getting Mila to do her first big filming trip, her first big expedition, and living it with us in this magical place.

It was also super exciting because, in the last twelve years, the filming techniques have evolved in crazy ways. With the experience we have now and the new techniques, having my vision and Victor’s vision evolve over the years, it was really exciting to see what the outcome would be. Besides that, we wanted to emphasise the family element – to tell a different story. I find that often, going on adventures, telling stories about them and making the stories special is just very redundant, so this was a great opportunity to tell our story from a different angle. Jerome Tanon, the director, is amazing for finding soulful moments and capitalising on them to bring real emotions, not just action and the usual adventure chat.

Do you feel like the relationship between the three of you has been captured on camera?

Yes. A lot. That’s actually the main thing about the film, to the point that it was almost frustrating. Sometimes you’re like, fuck, all those lines I did, and they’re not in there. But that story element is so important.

Does the relationship between you, Victor, and Mila change in the backcountry compared to how it might be during everyday life at home?

It’s for sure different. With Victor, we are used to it. It’s our job, we know how to handle it and it’s not the first time we do something together, but with Mila… She knows me as Daddy, she doesn’t know me as me in my world, my projects. But, on this trip, she became more one of us. In the beginning, it was trickier to find that relationship level between the two of us. We were there to do a proper mission, and she needs to be an adult about it. At times, she was scared and reacting to that fear, so some moments in the beginning were quite tough. But she evolved and found her place amongst all the rest of us who are used to doing projects like this. This trip was kind of the door between our relationship of being father and daughter to Xavier and Mila, from teenager to adult.

Did you find it hard as a parent to watch her do something you know can be really dangerous?

No, haha, it was the opposite, like, come on, move your ass! A lot of stuff that seems so easy for me and so basic… she was scared of it. But I told her, you’re not risking anything. I think it was more about other people putting in her brain, “Be careful; Xavier is going to make you do some crazy things, and Antarctica is so far away, it’s so dangerous.” She had this in her head and was a bit on the back foot. She just had to do it on her own to form her own opinion about it.

With Victor, we are the same. We push each other in a good way. And very quickly, we go like boom! We go pretty crazy, and that happened from the very beginning of the trip. Second line, we’re doing something super exposed, and we had to be like, okay, let’s be clever. And with Mila… it’s a bit early to say. I think she is the same as us. I think we have something in our family where we can stay calm-minded with risk.

How much planning goes into something like an Arctic snowboard trip?

This one was four to five years. It’s a lot of money to go down there, and there’s been political change of management and stuff, as well as different perspectives on the film, so that’s why it has been a long process.

There are so many aspects to freeriding, but you seem to have made your mark on the sport with the type of terrain you ride and the way you approach it. Was that a conscious decision to do things differently?

I like this kind of terrain and the fact that it is close to the sea. I feel safer dealing with the snow quality. I’m very scared of avalanches because of what has happened to me in the past, so if I can take down the level of avalanches, I will appreciate any adventure I am doing so much more. More often, I am ready to ride snow that will be less powdery because I will be less scared. If I’m not scared, it’s a lot easier to enjoy every moment of it. If I’m scared, I need to be careful about everything.

I remember when I was a teenager, I was only attracted by the mountains that were far away. I was in the resort, in the Pyrenees, where I grew up, like, “oh shit, I want to go to this and that mountain”. That’s how I felt from the very beginning, to be out there and to go and do these adventures. Thinking about my background in snowboarding, doing a bit of alpine, boardercross and freestyle, which gave me really good board control, riding big lines just fits. Riding fast and in exposed terrain has always been quite easy for me. I’ve always loved the mountains and mountaineering, so bringing that all together was quite natural.

In a resort, a big powder field with half a meter of pow can be so scary. I am absolutely terrified and hate it, whereas something super steep that has been running quite a lot, where you have lots of hiding points, I am going to feel right at home.

Freeriding and backcountry snowboarding have rapidly grown and evolved over the last ten years. What are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen in the sport over your career?

There’s been a major change with splitboarding. When Jeremy came out with his movies Deeper, Further and Higher, that helped trigger the change, and I think it came at the right time when people needed more connection with nature. I think that’s what it comes down to. I love the skate culture and everything, but for me, snowboarding, the essence of snowboarding, has always been about riding powder. It’s such a strong element that goes beyond the sport and the connection to nature, the love of that surfing vibe, all of these things combined. I was happy to see people becoming attracted to nature again thanks to splitboarding, getting outside the resorts and cities and seeing what’s out there. Adventure.

Everything is becoming so virtual, and the more it does, the more we need something intangible. Being in nature is the perfect opposite of the world where everything is tangible, constant, and fast. In nature, things are intangible. You need to adapt to them, accept them, and be accepted by them. We were born there, and the more technology takes us away from it, the more we are going to want to go back to it.

What direction do you see it going in the future?

I think the phenomenon will just carry on. Things are just getting faster and faster, and technology is taking crazy new steps with AI and stuff. It all just seems like soon we are going to live in a non-physical world, and therefore, we are going to need more space. For that, snowboarding is amazing. Get out of the resort, have no one around, and have that feeling of quietness and calm, being away from society.

What goes through your mind when you plan trips like the Antarctic one and when you are at the top, ready to drop in?

There is so much pressure that goes into these trips when you’re down there, and you start doing stuff that you went there to do, like bigger lines that you were dreaming of. Coming back with results, but then at this moment when you are at the top, you’re strapping into your board, things are good, snow is good, all the elements are there, that’s the moment when you can go fuck yeah, that’s it, we made it, feeling the board under my feet and it’s game on.

Do you think your approach to pressure in the backcountry changed over the years?

I think I manage the pressure better now. Thinking back to when I was younger, it was more about proving yourself, so you go in thinking less. You know yourself less. Now, I know what works. I know what is a good moment. I think, in a way, I might be a bit less technical than I used to be with my snowboarding, but in my head, I feel stronger.

Is there any advice you would give on managing pressure when out in the backcountry?

Everyone deals with pressure differently. The way I do it, if I’m scared of something, I try to analyze it from the point of what’s going to be the worst-case scenario, what is the worst that can happen, and that makes me understand if my fear is a good fear or a bad fear. If it’s a good fear and I am scared because it’s normal, you don’t want to fuck things up, there’s a very clear path of things to do, it’s going to work well, and it’s going to be great. Take that fear into consideration but don’t let it eat you. But, if it’s a bad fear, and you realize you are scared because you have no control over the situation, over the terrain, over anything around you and that you might fuck yourself up pretty bad without many chances of getting out of it, you shouldn’t drop in.

It’s really really important to develop your own way of analyzing things so you’re able to know if you’re pushing yourself too much, to listen to yourself. I know that it takes years and years to learn patience and the art of turning back. And that’s the hardest thing, because when you’ve been dreaming of a moment with your friends for years, riding powder, and today’s the day, there’s sunshine, there is so much powder, all your best friends are there, that’s when it’s difficult to take the right decision without getting blinded by joy and happiness.

Do you think you’ve become a more confident or cautious rider?

I’m very cautious, but when it’s good, I’m very confident.

You’re known for riding some of the most extreme and technical terrain in the world, but your “How To” YouTube series seemed like a real change of direction. A lot of it was very relatable for the average backcountry rider, and there was a big focus on safety. What made you want to create this series?

Safety is something so important, and I feel we have this duty to educate people on it when we are getting people to dream about the perfect runs and the perfect conditions in the most exposed situations. It’s good to know what it takes to get to this moment and what technique you need to manage it. And, with the rise of social media, seeing how content was just being consumed and thrown around, I wanted to build something that was both useful and timeless, not something that goes viral and then straight to the garbage.

I think, in the backcountry, you constantly see people who have no idea about the risk that they are taking, and that’s one of the biggest problems. People see ski resorts in the way that, it’s a ski resort, so everything is safe even if they have heard about avalanche risks. They don’t want to spoil their holidays with such thoughts. There’s a lot of work we have to do to help make people more aware, and that job will always be there, even if many people are well-equipped. Snowboarding is a sport that you cannot ever really know or have too much experience with because snow itself is a tricky element.

Backcountry gear and safety equipment are now more advanced and more affordable than ever before. Do you think this is making the sport safer, or do you think it’s encouraging people to take more risks and educate themselves less?

It’s a controversial question but I always tend to think that safety gear helps more than it doesn’t. It saves more people than it gives fake confidence to people. It’s for sure true that many people have their avis and think they will never die in an avalanche, but at the same time, it’s also true that it saves so many people. I’m all for promoting it, but it’s good to remind people that it takes more than just wearing the backpack to be safe. A lot more.

At the end of the day, when you go freeriding, even if you’ve done an avalanche course, you still need so much more. The mountains are one of the last fields of life where you are responsible for yourself. You have to learn to read the conditions, you have to learn survival techniques, and you have to be smart. If you make a bad decision, you can have a fatal accident. And compared to society, where everything has been made safe proof for anyone, where everything is really regimented, in the mountains, we can still push things on our own terms, and that is what makes it so special.

Can you talk us through the kit you always bring into the backcountry?

If there is powder, I always ride with an avalanche backpack, shovel and probe. I always have my helmet and often also a small light ice axe. And a communication device in case I will be going to a zone where there is no network. But I think my most valuable tool is my mindset. Every single run I do, I tell myself that it’s going to slide. I take that for granted. It’s not like maybe, one day, it could slide: it’s going to slide, and I ride like it’s going to slide.

Has this changed over the years?

I used to be a lot less prepared. I think the changes come mostly from my knowledge and what I’ve seen over the years, but also from the change in the general culture. Twenty years ago, in Chamonix, it was very uncool to ride with a helmet. People would laugh at you if you had a helmet. Now, the culture is completely different. So, in the long term, messages go through even if they take a long time to sink in.

How have apps like FATMAPS or other ways of assessing terrain changed your approach to planning backcountry missions?

A lot. It’s such a good tool. It is really helpful when you’re exploring. You save so much time.

Have there been times when you discovered completely new zones or hidden lines because of this?

Totally. You can also find exits, analyze what kind of exposure there is… it makes you understand the mountain range much quicker than a paper map. It’s really good and super easy to read. I would recommend it big time for beginner explorers, too, for any level really. It’s super interesting to know and understand the terrain you’re going into.

Compared to most people, you spend a lot of time in far-out locations, where the effects of climate change are more acutely felt. Spending time in the Arctic, Alaskan backcountry, and high alpine over the years, what changes have you observed in these environments?

Any time there are glaciers, that’s where you can see the effect of global warming the most: two years ago, the glacier was here, and now it is there. In ten years, it’ll be over there, or it’ll be gone. In Antarctica, it’s the same. A bit.

This time, we went earlier in the season than twelve years ago. Twelve years ago, in November, it was not guaranteed that you could sail through the peninsula because there would be ice everywhere. This year, since September, there was no ice anymore. The season was so much more advanced than it was back then. We went to this one bay where we filmed 12 years ago. Then, it was 100km to get to the end of the bay, and everything was filmed with ice. This year, there was nothing. Nothing at all. Not a single piece of floating ice. You could just take your boat and go to the end of the valley, and that was pretty mental. We also visited a Ukrainian science base. They have measurements from the last 70 years, using the same machines, and have been measuring a 4.2 degrees increase in average temperature… They told us they could see such a big change now, not only with the ice but also with all the fauna and flora. All the penguins from the north have moved south because there is no more ice in the north. They used to have one colony of penguins in the south, but now they have hundreds of colonies.

Have you noticed the effects of climate change on backcountry safety? For example, in terms of snowpack stability, seasonal weather patterns being more erratic, etc.?

People often think that the fact that temperatures are more variable results in more dangerous conditions, but, in my experience, which is mainly based on riding high alpine terrain, I find that the snow that you are going to get is safer. Maybe you have less consistent good snow throughout the season, but very often, you get this huge amount that will lock the whole snowpack. The snow level is higher, so you will get stickier snow up high. Often in winter, when it snows down low in the higher alpine, it’s very cold snow, so there’s less snow, and it’s less sticky. There’s more ice higher up, a lot more rocks, and a snowpack that doesn’t stick that well, but the closer you get to the snow and rain level, the more stable it will get. So, last winter, when the temperature levels were quite high, it was really stable.

But it’s not a question of the softness of the snow. It’s more a question of temperature, which results in the shape of snowflakes. When it’s closer to zero degrees Celsius, there’s more humidity in the snowflakes, and usually, it’ll also snow more. There will be more accumulation, and the snow will be denser, so it will hold itself together better. And when you get a good layer of that, it will quickly make a shell, which holds itself together, instead of making small patches that are all very inconsistent snowpack. Often, in the Alps, you have a lot of snow at the beginning of the season and then no snow for a while. It’s that very first snow that will transfer itself to a very bad layer of assets, and then you have that until the end of the season. Then, whenever you have a long run of rain and high temperatures for a few days, everything that has to come down comes down, but after what remains will be pretty safe. The crazy weather patterns often do that: they flush everything down and create a fresh canvas and, in a way, heal the bottom layers.

But, to be honest, you could know everything about snow and learn the same things as someone else in the same environment but still see things differently. So, everything I am telling you is related to the way I see it and the kind of terrain I am riding. If you take different types of terrains, they would have different meanings. What’s true in my case is not going to be true in Norway, Utah or Colorado, where there’s a really dry snowpack.

There is an environmental cost to people going skiing and snowboarding – in terms of travel, the production of equipment and clothing, the infrastructure in resorts, and so on. On the other hand, there is a strong correlation with people who are active and engaged in the natural environment feeling more connected to it and more determined to protect it. It’s a bit of a tightrope, managing our environmental impact while making sure more people have access to nature and the outdoors. How do you feel about this sort of contradiction?

As soon as you talk about the environment, you’re going to have contradictions. The way we live contradicts nature, and I think we all have things where we can easily make changes that don’t cost us too much.

Some people will be totally happy not eating meat or traveling only by train, and for some people, it’s going to be doing something else. There are so many ways to do your part to protect the environment, and what I have learned from the past is that we need to keep living our lives because that’s what we were designed to do – to enjoy our lives, to set goals, but to do it within reason.

Whatever our lives allow us to do better, we should do it. It is difficult to talk about because it’s a controversial subject that can get some people super-triggered. But, if you’re asking me, should people not go snowboarding, with transport having the biggest impact on the environment in the ski tourism industry, should people stay home for environmental reasons? I think I’m leaning towards no. The more people are connected to nature, the more they discover its beauty, and the more they will want to protect it. I know this isn’t going to be everyone’s belief, and I respect that as well.

Do you think athletes like yourself have a social responsibility to speak up on climate issues and use their platform to spread awareness and promote change?

I felt like I did, and I feel like I do, but it’s tricky. I have got quite hurt and called out on social media as soon as I would talk about climate change. People would be like, “You’re sponsored by Audi, so how the fuck are you allowed to cry about our glaciers”. Like ok… The number of bad messages I get sometimes. So, now, if I post something about climate, I post it and don’t look at the comments because it’s hurtful to read. It’s like a personal attack towards me.

I guess it’s easy to insult people when you can hide behind a screen…

Totally.

Thinking back about your career, did having children change your relationship with snowboarding and riding backcountry?

Mila is 18 years old, and my number two and number three are three and five, so it definitely puts that extra pressure on me. You don’t want anything to happen because they [the kids] are counting on you. So yes, I think I’m more strict about not doing stupid stuff and making the right decision, which is good. In freeriding, it’s nice to have a good reason to want to come home, and that’s the best reason I could have. Not to gamble on my life.

But, from seeing a lot of my friends who are the same age as me, I think the biggest problem for people is that you go less out there. You do less of your own thing. And because you go less out there, you’re less fit, you’re less agile, and you become more scared of everything. Having kids doesn’t change things that much. It just makes you a bit smarter.

Is there anywhere you still haven’t snowboarded that you would love to go to?

Not really! Well, there is this one island in Japan I would like to go to, and it has a volcano that comes out of the sea and looks pretty cool.

Finally, if you weren’t a professional snowboarder, what career do you think you would have ended up with instead?

I have no fucking idea! I don’t know… I wanted to be a cook for a while, but that was when I was very young. It’s crazy because I’ve been a pro from a very early age, so I’ve never really worked in any other way. I love building stuff. I love wood, so yeah, being either a carpenter or architect or maybe a bit of the two together would probably be the field where I would be super happy.