0

£0.00

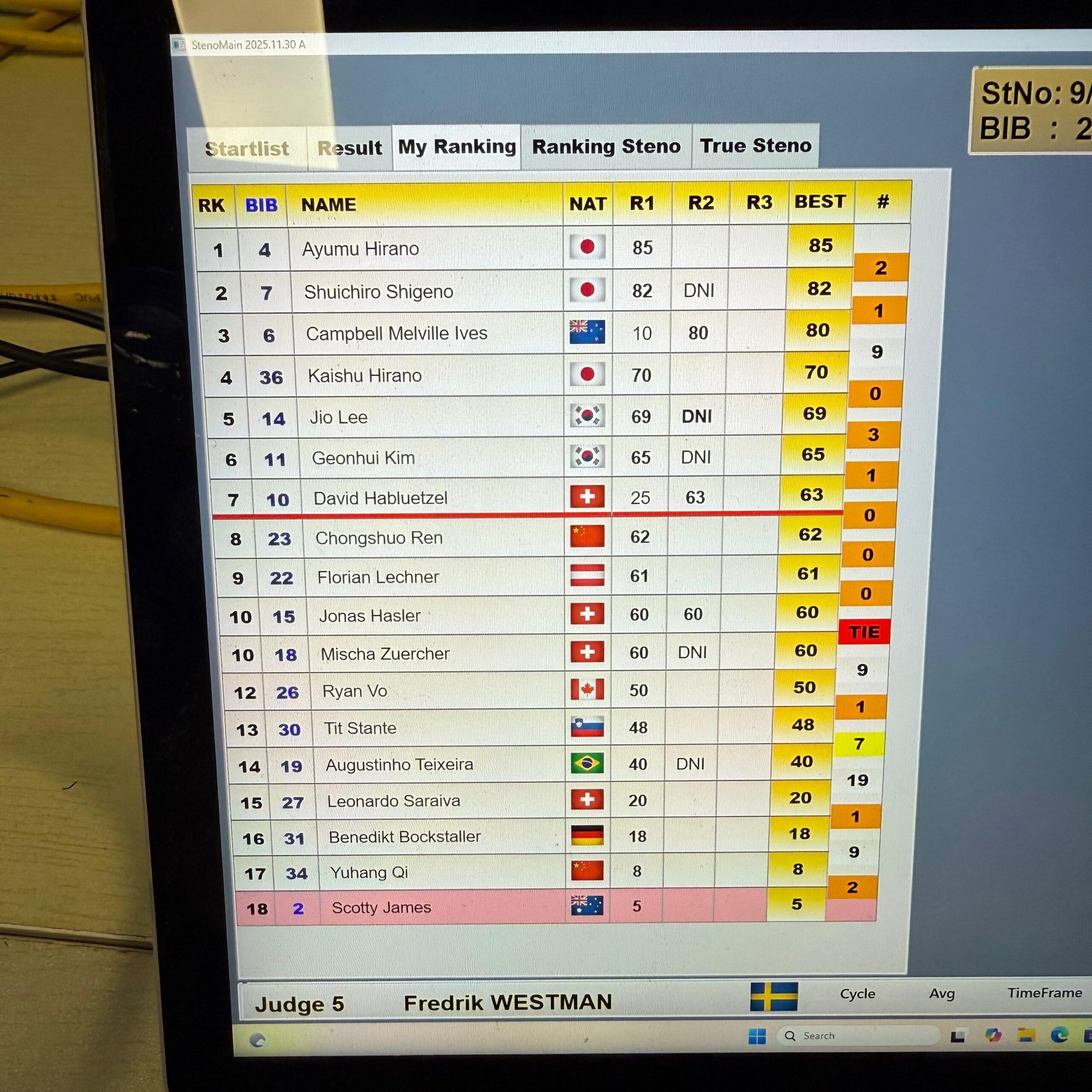

A Swede, a Norwegian, a Canadian, a Japanese, a Slovenian, and a Brit sit around a table. It’s not a joke, it’s a judge panel.

The World Cup snowboarding competitive season is about to kick off, but with the start of the season also the rest of the grass root and national level competitions.

The outcome of an event depends on the time, place and the judge panel – Fredrik Westman

The snowboarding community has a long history of criticizing the competitive side of the sport, the Federations, and more specifically, FIS. You can refer back to the numerous articles written about Terje and his protests, the birth of the TTR and evolution into the World Snowboard Tour, and the recurring disagreements between the World Snowboard Federation and FIS.

There are many reasons of these disagreements and polemical discussions: political, economic, cultural, and also, let’s not forget, subjective opinions of where the sport should go as a whole.

And it would be, of course, weird not to mention the polemic of the inclusion of snowboarding into the Olympics. “Is it good for the sport?” or “Is it bad for the sport?” A few years later, is snowboarding better off because of the Olympics? Again, there is plenty written about the topic on both sides of the fence, and we are not here today to judge either of those. But rather, to shed light on one of the most misunderstood jobs of the whole industry and one that is crucial and inherent in competitive snowboarding, and arguably to the progression of the sport. The snowboard judges.

During the 2022 Olympics, the hate, disrespect, and misunderstanding of the role of the judges was brought to the extreme (and the bad one) from the industry, athletes, and snowboarding community. Also, by 230 million “Chinese retweets”.

It’s still difficult because it becomes a “subjective objectivity”. We don’t have a style criteria, and different people (judges) like different styles. – Fredrik Westman

And after that, it became obvious that there is a need to better understand, humanise and talk openly about the roles, limitations, and responsibilities of the snowboarding judges, the event organisers, the athletes and coaches, and last but not least, the community.

The nationalities of the judges vary in each contest, and they are not just a faceless flag; they are people with a name, a life, an education, an experience, and an opinion. Which makes them human. We will get into that later, but first, I want to dive into an interview I conducted with Fredrik Westman, the Swedish snowboard judge who is one of the active World Cup judges with the longest experience in the stand.

Hey Freddie, to start things off, could you give us a bit of context on how judging is set and why snowboarding is a bit different than other judged sports?

When I train other judges at a judge clinic I often like to explain the story about the aerials: In the 80’s, this was the coolest sport around, but the sport evolved in a way that the skiers became more and more specialised: the trick itself has a determined difficulty score, the tricks are defined as how they should be performed and the opportunity of creativity is therefore lost. This eventually killed the hype around the sport.

Snowboarding did everything differently: we stood sideways, we had different clothes, we listened to different music. We took everything skiers had and made sure we were as different as we could be from them. So, of course, the way we started to judge competitions had to be different too.

Nobody wanted to be told how to do a 360, and the judging of the sport didn’t intend to do that either. We have tried many systems over the years, but they have always been based on criteria.

Like the “DEAL”: Difficulty Execution, Amplitude, Landing.

This one has also evolved, and as you can find in the Judge’s Handbook, the criteria we use today are Difficulty, Execution, Amplitude, Variety, and Progression.

However, it’s still difficult because it becomes a “subjective objectivity”. We don’t have a style criteria, and different people (judges) like different styles.

What are the things you’d like to explain about judging that often get lost or aren’t widely known, but you think they should be?

First of all, the basics and the differences between SBS and OI.

SBS stands for section-by-section scoring. OI is overall-impression-scoring. In overall scoring, all the judges give a number for the overall performance based on the criteria; the highest and the lowest scores of the panel get dropped. And the average of the other scores is the final result. This is the system we normally use in halfpipe, and sometimes in slopestyle too, depending on schedule constraints of the event, but nowadays it is less common there. At least for the World Cups or higher levels.

The one thing that is very important to understand here is that points don’t matter. Points are simply our tool to establish and position riders in a ranking.

A common complaint we get from riders is “My score is too low”, but when you ask them if they are happy about the ranking position for what they did in comparison with what the other riders did, they often don’t have an answer. That’s because they forget or don’t realise that the points don’t matter, it’s just our tool to position them in the ranking when comparing them to the other competitors.

For example, take Shaun White’s “perfect 100 score” at the 2012 Winter X Games. There were tens of thousands of comments online about how it was wrong to give it 100 points. “He had his hand down on the last trick, can’t be a 100 then”. ALL of these comments are fundamentally wrong, and show the little understanding people have about the judging. Shaun’s run was the last one of the day, and it was the best run so therefore, it’s perfectly OK to give him 100 even if he had some instabilities.

When we use the SBS system, we divide the course into sections. Depending on the course design, a section can be one or two features. We assign judges to the different sections, and we also have a few overall judges.

In this case, the actual points matter more. Because of the mathematics of it.

With the SBS system, it’s really important to work with the ranges on the different sections. A similar trick performed on kicker 1 or kicker 2 should be given a similar score. Each section should be worth the same. As I said, here the actual numbers are more important, and it’s a more complex process to establish the ranking. But remember, these numbers are still only relevant within the same contest. The range can differ between contests.

Tell us about the live component of the judging.

Yes, this is the second thing I’d like to explain. When we are judging, we do it in real time: live. We have a matter of seconds to make a decision, a calculation, and take note of what went down before we give the score. Because it’s on live TV, we have a very demanding time pressure, and one thing that is hard to believe from some people is that we don’t usually get replays.

We judge what we see when it’s happening. Which brings me to the next point: whatever is shown on TV can be very different from the images the judges get.

To be able to judge objectively, we need to see every rider from the same angle, and that angle should allow us to see the amplitude, the landing, and the take off. And this would make a very boring TV show. So we often have a separate TV feed from the actual show, and if we don’t, we are at risk of missing details of the performance. But also, depending on the angle that we are given, we can miss out on details. But at the end of the day, we can only value what we can see, which is a very important factor to understand for the riders, the event organiser, the TV production, and everyone else.

Take for example, the Olympics 2022 with Max Parrot’s infamous knee grab. From the judges’ feed, it is really impossible to see that he has a short grab that goes into a very strong knee hook. It looks like a stomped trick. But from the other TV-angle it is so obvious that it was not. But when that other angle came on as a replay, the score was already in, and then it’s locked and official. We tried to fix it right away, but the rules didn’t allow us.

And then of course we got f*cked by everyone online, including 230 million Chinese tweets! I am so disappointed by how much hate this community could produce. Even from people I think should know better, showed a really bad side of themselves.

I have watched the judges’ TV-feed on that trick probably 100 times, and even if you know it’s there, you can’t see the knee hook! We had riders and coaches to watch it, and they all agreed that it was an unfortunate angle that made the trick look OK.

We all like to play judge from the sofa, and I can understand that having all the angles possible, the replays, all the time in the world, and zero pressure is a very different experience than what the judges are experiencing on site.

I think it’s important to understand that the TV production plays a huge role in telling the story to the audience and also to the judges, as it’s edited and curated, and like everything that is edited, it always tells a story.

That’s the reason why the judges need the footage to be as raw as possible. This poses a logistical and cost problem for the event organisers and the producers. What are you doing about this?

A couple years ago, FIS brought together judges and TV producers to try an iron out discrepancies and find solutions to better serve the needs of the judges as well as to be able to deliver a good TV product.

It was a really good opportunity for all of us to be able to better understand both sides and see the work, needs, and limitations on each side.

One thing that we all often hear and probably wonder is the +180 evolution of the sport. The ‘spin to win’. Does SBS reward trick difficulty the most?

Not quite, the difficulty of the trick is a factor, but as I explained earlier, there are other criteria. When we are judging a feature, it’s true that we have a “cheat sheet” according to the trick. We know that a 10 should be in a specific range of points and a 12 in another range. But it’s still a range, so a smaller spin can still score higher as difficulty to the trick can be added by the kind of takeoff, the grabs, the bones, etc.

A good example is Rene Rinekanga’s in Beijing Big Air earlier this season. He landed a nosebutter backside rodeo 14 in the competition, which was the highest single score of that event, even when other riders landed 1980s. In this case, the takeoff is risky, hard, and blind, which awarded him the extra points for the difficulty without having the biggest spin. And it scored high in the Progression criteria too.

You see a lot of this added difficulty in Eli Bouchard’s tricks, just to give another example.

In the past year, we have seen a heavy increase on very progressive takeoffs, which now means that a camera for the in-run and the take-off is needed, and it should be mandatory, to make sure we can see it all and score the tricks accordingly.

Bringbacks, holdbacks, tweaks and harder grabs are also a way to get more points without adding another spin. However, at the end of the day, the outcome of an event depends on the time, the place, and the judge panel. That’s the downfall of the criteria: It’s open for personal interpretation.

Hmm… so this means that the criteria the judges use are what dictate the evolution of the sport. Should the judges drive these criteria?

No, the community should decide them. The judges implement them, but the community should decide the direction of it.

And how is it all decided? Who, when, and how decides that the criteria or the system are outdated?

When you decide to compete for FIS, you are accepting that the nations will decide, craft, and push to tweak the rules. The judges, on the other hand, need to be part of the community and listen around them as much as possible to know what’s hard, what’s cool, and where things need to change.

But you, as a judge, don’t decide or change the rules. It’s very easy to say the community should make these decisions, but how is that truly and practically done?

The judges need to be updated. Watch a lot of snowboarding, read a lot of media, talk to riders, coaches…

And then we go to judge clinics at least once every other year, as it’s mandatory to keep our license, but many of us go every year to bring all the knowledge and feedback from past seasons.

These clinics are important because it’s when we are trying to reset and make us all equal, we need to all be on the same page to be able to judge well during the season.

All year round, we have global groups where we share what comes up, the new tricks that pop up on social media, and we look at them repeatedly and discuss them.

And in the last few years, we have arranged a few athlete-judge clinics to discuss the progression of the sport and where we all collectively would like to see it going.

But, isn’t that why you have different people on a panel, to have different opinions?

Yes, of course, but we need to have consistency throughout the year. Riders train all year, after how they get judged and scored. If we are not all doing it in the same direction, it would be really hard for them to know what to do and would get different outcomes without knowing why.

It sounds like a high responsibility job that can go wrong very easily, and when it does, it has such a high and often negative impact. So what do you like about it so much that makes you keep going back season after season?

I guess… I love the sport, I love seeing the places. And if you are going to be judge, you need to have thick skin and not take anything personally. It’s not pleasant to get your work criticized, and it can be really tough. Many people have stopped judging because of it, and it’s particularly hard when it’s big names like old riders, talk show hosts, and follow filmers or old glory movie producers. I believe they should know more about how it works, but sometimes it just feels like they want to have social points themselves.

So… why do you do it? Why are you still a snowboard judge?

I don’t know. I love snowboarding; it’s a way to be part of it; I love travel, and it’s a way to make new friends. But I actually want snowboarding to progress in a good way.

I was one of the last ones to join FIS events as a judge because I was afraid. It is a big shift, and although it can also have a lot of benefits, I was afraid it would make the sport boring.

And has it? Has FIS made snowboarding boring?

I think that they are actually doing a pretty good job. I think that eventually, even if it wasn’t FIS, the competitions would have been going down the same route of “professionalism” either way. I think the outcome would have been very similar.

They have a structure, the rules, and consistency. They have the capacity to keep going to focus on the sport itself rather than securing the continuation of the organisation. Which is a good thing.

Right. Interesting. So, where does the Snow League come into this? You, as the head Judge of the brand-spanking-new Snow League, have been part of creating the format and curating the judge panel. How is that done, why is it good or different from FIS, and how do you ensure consistency and progression at the same time?

First of all, for the panel, we wanted to bring ex-competitors like Chad Osterstom and Guillame Morrisette as they have the first-hand high-level athlete experience and add another perspective to the judge panel.

I also love that they have introduced Connor Manning, who used to be a former World Cup judge, to be the bridge between the judges and the media, and who can explain what’s going on and how decisions are made in the judging booth.

The Format for Snow League is based on the premise of making it exciting and truly highlighting the riders. The head-to-head format is exciting to watch and easier to understand for the audience.

However, this is the first season, so we are still developing and polishing it. For example, we saw in China that the riders were getting tired at the end of the day if they had too many matchups during the finals.

The good thing is that for Snow League is easier to steer the ship and make progressive changes to the structure and format compared to FIS. It’s a smaller organisation, so they can change faster if it means making the competition better for everyone. And, also, they have a lot of great people in the right positions, for instance, Sandy MacDonald as Head of Competition, who has extensive experience as a judge and technical director, but most importantly holds the love of snowboarding very close to his heart.

Another question I’d like to ask you, as one of the most experienced judges in the game, is how the system guarantees the incorporation of new blood and fresher perspectives to the panels? What is the journey, and how can somebody get to judge at the World Cup level?

Well, that is one of the problems; it takes commitment to become a high-level judge.

You have to do a course, and judge low-level events for a while, and then a clinic, and then continue to judge higher-level events. But it takes a while.

At least two to three years. But it’s hard because usually the payment is low, especially in lower-level events, and if you live in an area where there aren’t many events, is also a problem as the budget doesn’t always allow for long-distance travel.

I love having ex-riders, young ones, to judge with. It’s really nice to have their input. It’s really good to have a fresh view on some tricks.

Do you have to be a former pro rider to be successful at judging?

No, of course not, but it helps with your trick knowledge, and if you can do the tricks is a benefit to it. You can get fast-tracked to the higher-level events because your understanding of the tricks is that much deeper. But you can also gain that knowledge in a different way.

What is the advice you’d give to someone curious and would like to become a snowboard judge?

Hang in there. It takes a bit of commitment, but once you’re in, it can be a really fun way to be part of the sport.

If there is just one thing you could tell to the riders and their coaches for this Olympic season, what would that be?

Attend a clinic. Get an understanding of how it works behind the scenes. Sometimes I am surprised that even high-level athletes don’t even know the criteria they are being judged on.

Thank you Fredrik, for your thorough explanation, the many examples, and a slight peek into the behind-the-scenes of everything that goes on in a split of second during a big event.

As a community, there have always been snowboarders who haven’t been very keen on the competitive side of the sport, yet we tend to be a very competitive bunch. Others are just against any structured and regulated organisation, and most of us enjoy every squeeze of footage, event, and trick we get to watch. Let’s not forget that snowboarding is a privilege and a joy that just a handful of us get to experience. We are all in it because we are passionate about it and, like Fredrik said, “being a part” of it is what matters. Whatever that may look like for you. Enjoy it in whatever shape or form you like, but above all, don’t forget to respect other people’s choices and work. Luckily, there is a place for us all, even if we don’t know it yet. But this is a story for another time.

Justin Befu on the responsibility and reality of guiding snowboard films in

Snowboard Big Air will be one of the most exciting spectacles at

Sign up for the very best in snowboard culture, get notified of prize drops, and receive our weekly essential news hit: The Friday Dump.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_189035576_1 | 1 minute | This cookie is set by Google and is used to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the website is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages visted in an anonymous form. |

| CONSENT | 16 years 4 months 12 hours | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. They register anonymous statistical data on for example how many times the video is displayed and what settings are used for playback.No sensitive data is collected unless you log in to your google account, in that case your choices are linked with your account, for example if you click “like” on a video. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Used by Google DoubleClick and stores information about how the user uses the website and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This is used to present users with ads that are relevant to them according to the user profile. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | This cookie is set by doubleclick.net. The purpose of the cookie is to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is set by Youtube. Used to track the information of the embedded YouTube videos on a website. |

| YSC | session | This cookies is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _pk_id.43969.7c7f | 1 year 27 days | No description |

| _pk_ses.43969.7c7f | 30 minutes | No description |